.png)

In Sub-Saharan Africa, fisheries represent more than an economic activity; for millions of people, especially in vulnerable coastal and inland communities, they are a vital source of food, income, and resilience. FAO estimates that, in 2022, Africa produced 10.6 million tons of fish, accounting for nearly 12% of global output. However, this foundation of livelihoods is under growing threat from climate change. Rising sea temperatures, shifting fish distributions, unpredictable rainfall, and more frequent extreme events are already undermining catches and putting households at risk of hunger and poverty.

The good news is that adaptation strategies exist, and evidence shows they can make a real difference. These include sustainable fishing techniques and climate-resilient aquaculture practices such as seasonal fishing closures, combining species at different trophic levels and use of low impact fishing gear. There is, however, a notable challenge: most of the agricultural adaptation studies linking to food security have remained in the crops sector. The few studies that link fisheries climate change adaptation to food security are focused outside the subregion.

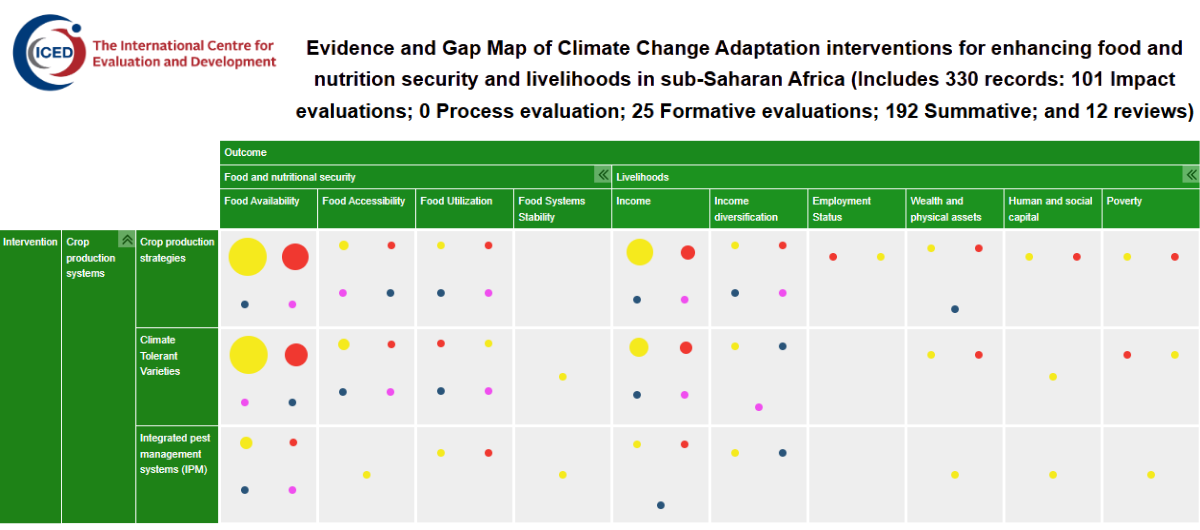

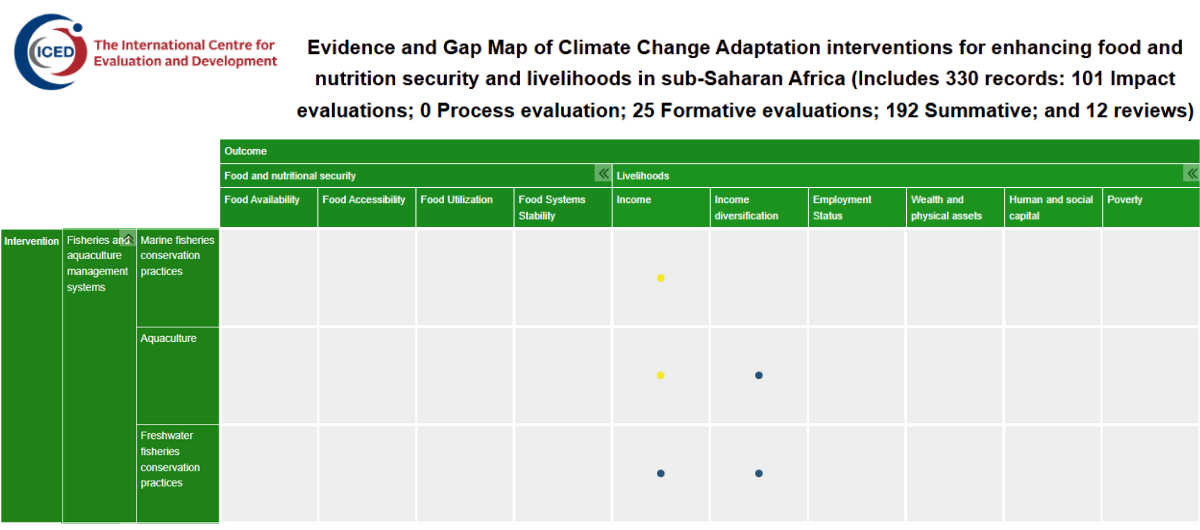

In reviewing the evidence for climate change adaptation in our ongoing Evidence and Gap Map (EGM), one striking gap emerged: fisheries are severely underrepresented. Currently, less than 2% of the agricultural adaptation studies in the map (i.e., 4 out of 330 included studies) address fisheries adaptation and its implications for farmers’ food security and livelihood.

Around the world, there are promising examples showing that adapting fisheries to climate change can improve food security and livelihoods:

Despite these insights, Sub-Saharan Africa is strikingly underrepresented in the literature. Most existing studies rarely link adaptation actions directly to household food security or nutritional outcomes.

We cannot afford to leave Africa’s fisheries behind in the global conversation on climate adaptation. For close to 500 million people in Africa, fish are not just food on the table, they are the difference between resilience and vulnerability. Researchers, funders, and policy makers must prioritize filling this evidence gap by commissioning short, medium, and long-term studies linking adaptations in the fisheries sector to food security outcomes. Generating such evidence is critical for shaping robust, evidence-based policies and programs that not only strengthens the fisheries sector but also bolsters food security in the region.